Mark Boyle, the former “Moneyless Man,” lives like a modern-day Thoreau in an off-grid cabin he built in County Galway.

Mark Boyle, the Irishman formerly known as ‘The Moneyless Man,’ has been challenging Western notions of capitalism and consumerism for nearly a decade. For more than three years, he lived in an off-grid caravan, grew his own food, and walked or cycled to get around, reconnecting with the land and its inhabitants — and not spending a single cent. He wrote his first two books, The Moneyless Man and The Moneyless Manifesto, about the experiment. Since then, he’s given lectures and a TED Talk on the gift economy and the importance of community; and in 2014, he bought a plot of land in County Galway, Ireland, (using book profits) to start An Teach Saor, Irish Gaelic for “The Free House,” which aims to share the joys of anti-consumerist living with others. A “free pub” and bunkhouse, The Happy Pig — built out of natural materials from an old pig pen — welcomes visitors to eat and stay for as long as they like, in the hope that they’ll pay it forward.

By last December, Mark was living off-grid again, this time in a tiny cabin he built for himself that doesn’t have electricity, gas or running water. He’s in the middle of another experiment: living without technology, which he’s writing about — by paper, pencil and post — for a Guardian blog that he doesn’t read (he has no computer, internet or mobile phone). Earlier this year, I drove the narrow country road to visit Mark so I could get a taste of “The Free House” and what living without technology is like. Here’s what he had to say.

SR: How did you start learning about environmental issues in the first place?

MB: When I finished my degree [in business], I was in England working for five or six years. I was managing an organic food company, called Better Food in Bristol, when I started to learn about ecological issues. I was dealing with suppliers a lot, and all the staff there were radical types like you get in health food stores. So I’d hang out and chat about issues. I learned a lot from people, and then I explored stuff on my own. One thing led to the next, and I was living without money.

Was there a specific event or experience that sparked the idea for ‘The Moneyless Man,’ or was it a more gradual process?

Over a number of years, I was exploring all the issues more and then came to the realisation that there’s a common thread in them all, and that was a separation from the natural world. The more separate we become, the less we know about the harm we’re doing. It’s about the degrees between the producer and consumer. When [the separation is] wide, then a lot of shit happens in between. When [consumption is] localised, the capacity for shit is narrowed. When you’re buying something from Chile, you don’t think about the conditions for workers, the ecological issues in terms of freighting, the pesticide use, the plastics, the factories, the roads, the flights, everything from start to finish. So the common thread I saw was this disconnection, and the thing that allows us to be disconnected is money. Without money, you can’t have a relationship with someone in Chile.

So it was the food system that first opened your eyes, and then you expanded out from there?

Food is the most obvious thing in our lives. Better Food was probably one of the most radical food shops in the UK, in that they’re almost entirely organic, whereas a lot of other places do a mix. But I remember walking in one day and it was just wall to wall plastic, and I thought, [the organic] is good, but look at all the shit that’s around it. It was like, I’m not sure what the question is, but this is not the answer.

How long did the moneyless experiment last, and what were the biggest lessons learned?

I thought it would be a year at first, but it ended up being three years because I was just loving it. I learned that, yeah, you can definitely do it. People often mistake that for me saying the whole world should go moneyless tomorrow. That would be impossible, and there’s no appetite or desire for people to live moneyless, so it’s a political and economic nonstarter. But I do think if we don’t start making a move back towards more localised living then ultimately we’re doomed. And even if it’s not an apocalypse straight away, it’s going to be grim, with the effects of mass extinction events and climate change and so on. We’re going to start feeling them… I think ultimately there are big changes in store for us at some point in the future, and that we need to start making the trip back home.

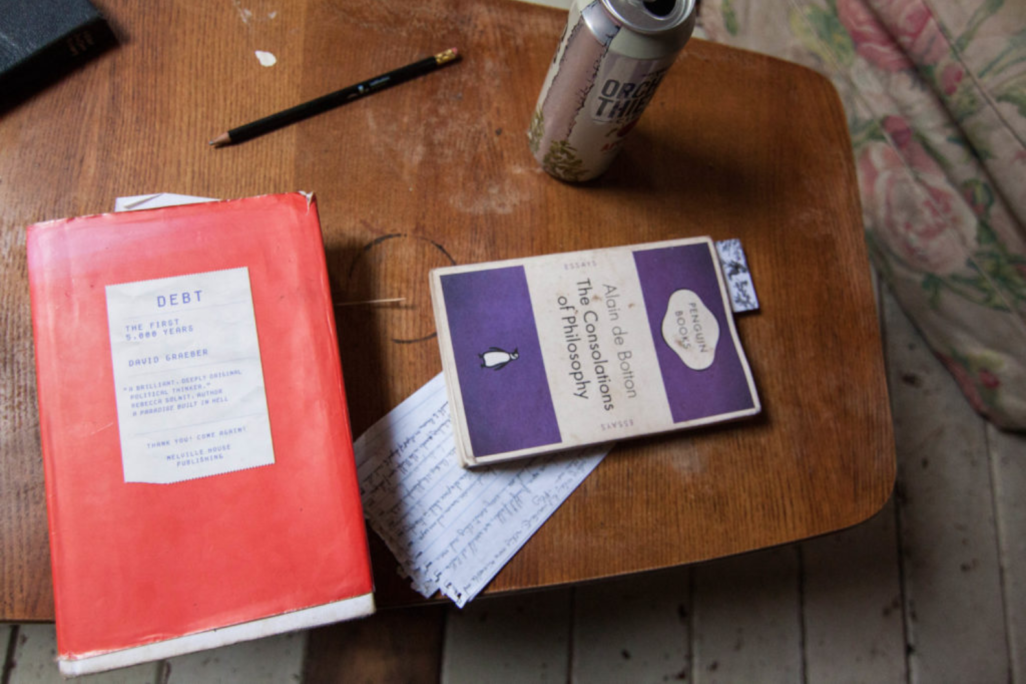

The shelves of The Happy Pig are filled with books on permaculture, economics and philosophy.

What does one need to live a moneyless life?

It was weird because like the day after I decided to live without money, I met this girl who stopped me on a cycle path and told me about a project she was working on out at [Roch Mill farm near Bristol]. [She asked if I was] up for getting involved in some way. I said “Yeah, but is there any chance of parking a caravan there to live in?” She said, “Of course, and you can volunteer there.” So already in a day, I had a place to stay. Three days later, I got a caravan on Freecycle. It just shows that when you commit to something you believe in ‘the mysterious one’ backs you up a little and rewards those actions. Usually not any more than you need, just barely enough. So it all kind of went from there really. I was eating off the land, foraging, and bartering a small bit, and skip diving when I’d be in the city for the weekend.

What was the hardest part about those three years?

The first few months. The insecurity of not having anything in the bank, or not even having a bank account and literally living minute to minute. I gave away all the money I had and maybe 90 percent of [my] things.

Do you have any stories of near-desperate situations that worked out in the end?

One day, I went into the city — which was a 20-minute cycle in — for an event or skill-sharing evening, and I left in mid-afternoon and hadn’t taken any food with me. I was already hungry. But then I met someone in the street, and didn’t even mention anything when they asked, “Do you want to come over to ours for dinner?” I was just like, “Brilliant!” I couldn’t buy anything, so if I didn’t bring [food] with me from the farm then, apart from begging for it, [I didn’t eat]. But things would always just seem to work out somehow.

Why did you eventually give up the moneyless life?

I felt like I wanted to give other people the opportunity to experience [living without money] in some way, so to create a project that would allow that. Ironically, my first book The Moneyless Man, had done quite well, so when I finished [the experiment], some agent told me there was quite a lot of cash she’d been [holding for me], because there were about 90,000 copies [sold].

That brings us to An Teach Saor and The Happy Pig. What was the inspiration behind this place?

I’ve lived in different places and always seen the cost of getting access to land. There are a lot of obstacles, and the people who most want to do it can’t get access to land because they don’t have the money. So when we got here, we had a strong sense of wanting to make it a place where other people could get access. We wanted to create a space where people could come and stay, for a weekend or a month or six months. People can rock up and stay as long as they want and eat and experience [this life]. In the summer, we have events. Sometimes in the winter, we have solstice parties. We’ve had lectures as well.

The lounge of The Happy Pig, built with local materials and a technique called wattle and daub for the walls. Nearly all the furnishings were donated, making the final price tag 20,000 euros.

Last December, you decided to give up technology, which you’ve been writing about for The Guardian. What prompted that decision?

Technology has always been a thing of mine, and money is a form of technology that has its [own] language and is an ax. The column is called Living Without Technology, but that’s just the shorthand, because I couldn’t call it Living Without Industrial Complex Technologies; that’s too long-winded. But my perspective is an ecological one. That’s my first, primary, concern. If we destroy the land base then there are no social issues to solve because there is no society.

If you deconstruct a plug socket, for example, I can tell you how you destroy an entire planet. You’ve got plastics in there — which is oil rigging. You’ve got PVC, copper, rubber, and lots of different little elements in the appliances [being used]. All those are made in factories, and factories need suburbs and industrial centres and roads to get to those factories. Into those factories, you’ll have a load of machines, which need other factories to make them. You need coal [for electricity] and power stations [to run it]. Once you put people in factories, they’re disconnected from the land. Once people are disconnected from the land, they need to use the money to get from the factories to pay for stuff at the end of the world that’s getting shipped to them via oil and the whole rest of the fossil fuel world. Look at one solar panel and I can tell you how to destroy the world as well.

I think I get the picture. Does this project have an end date, or are you hoping to be done with technology for good?

Hoping to be, yeah. If anything, [I’d like to get] more and more primitive, and to keep growing my hair out.

What’s the next step after this?

Death probably! We’re all going to die sometime. But no, my thing at the moment is trying to get support for some re-wilding projects like the Cambrian Wildwood Project in Wales, which is linking up a few existing woodlands and wildlife corridors. The end goal is about 7,500 acres in the Cambrian Mountains. They want to introduce species in there again and restore the ecological health of the whole place. Their plans are probably the best plans I’ve seen.

Most things don’t make sense to me anymore, even the humanitarian things. I just think pffft, most of them are still destroying the planet even if I support them. But one thing I can always say is a good thing is creating wilderness and places for wildlife to be. No matter what happens to the humans, that’s what I want to see happen. So that’s where I’m putting my energy now, because it’s the only thing that makes sense to me anymore… [I wrote an article about it, which will] hopefully reach somebody out there.

Looking over the bar is a pine marten, a relative of the weasel and badger, which Mark found as road kill and got stuffed to help people reconnect with the native inhabitants of the land.

It is interesting that your message is getting out there using technology

Yeah, yeah, for sure. I can totally get a lot of stick for that. It is ironic in some ways. But from my point of view, if the thing didn’t exist in the first place I wouldn’t be bothering to write the articles. It’s kind of like you’ve gotta work with the world you’re in while trying to keep your own integrity intact, and living the way you want to live.

Do you feel like you’re almost where you want to be?

I’d say I’m probably 10 years away. For example, if it’s catching fish, I’d like to do it with a primitive fishing rod. I’m trying to do everything from scratch and the devil is in the detail. You can fish with a fishing rod, and I have no problem with that, but it’s still kind of using an industrial tool if you’re using a conventional one. [And I’d like to] forage more as well. You can never know enough about foraging.

But living moneyless is a lot easier than being a rocket scientist or a brain surgeon in the city. Even crossing the road in the city takes navigation. If you think of all the complexities that make a city function, that requires masses of resources and different people with different skills. But here, you walk down the lane and there’s a few berries on the side of the road and you pick them. And there’s a few ramsons [wild garlic] over in that patch where you always get them from, and you pick those. It’s not that complicated.

(This Q&A was originally published in September 2017 on the Transition Bondi blog)