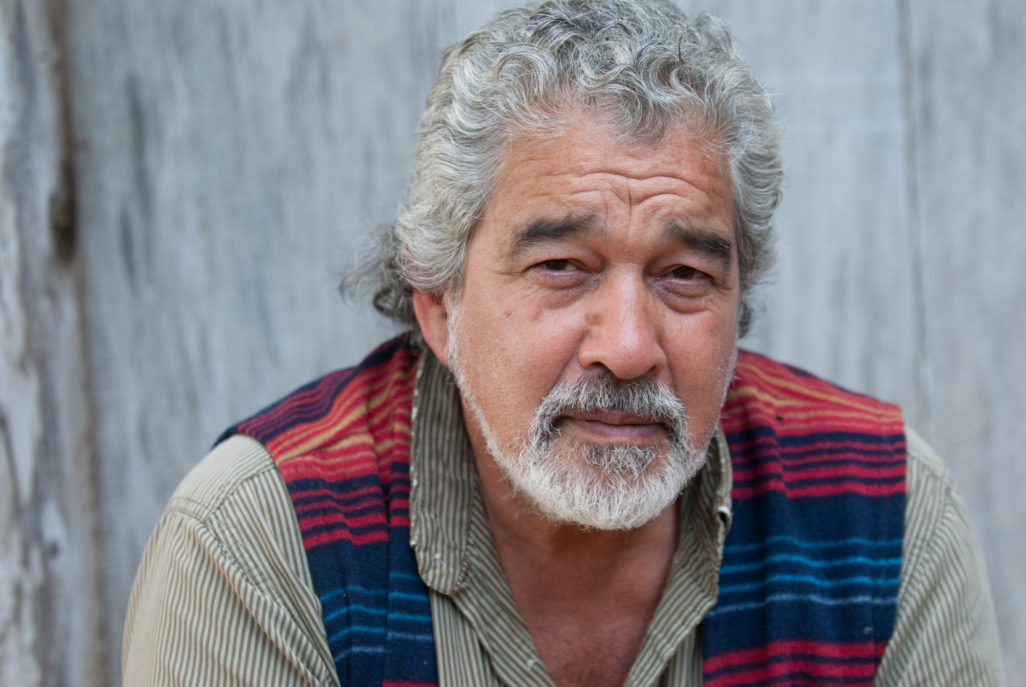

Kuuyang-Lisa White, who operates the Gin Kuyaas gift shop in Old Massett, wonders why her people have to import wood to build homes in Haida Gwaii. Photo by Serena Renner.

After decades of struggle, the Haida Nation signs a landmark agreement with BC and Canada aimed at autonomy.

A few days before one of the biggest milestones in the Haida Nation’s struggle for self-determination, I was having coffee with Guujaaw.

We were seated on the patio of Jags Beanstalk cafe in Skidegate, near the southeast corner of Graham Island, the shield-shaped northern base of the archipelago of Haida Gwaii. Guujaaw, the Hereditary Chief Gidansda and formidable former president of the Council of the Haida Nation, was sipping away the sad face shaved into his cappuccino foam. “He thinks I’m grumpy,” Guujaaw said, gesturing to the cafe’s owner, Jags Brown.

Guujaaw didn’t seem grumpy, but like he had something on his mind.

After a 15-minute conversation about climate change (“the jet stream is all out of whack”) and the wonders of Haida canoe technology (old designs — believed to be gifted from supernatural beings — are symmetrical “within a sixteenth of an inch from side to side”), he landed on the heaviest stuff: colonization, criminalization, residential schools.

He recalled being put in jail for two days because he and his sons caught 27 pink salmon without a license on a river where 750,000 were taken by license holders the same day.

“And the reason for that is they wanted to sever those ties to have their way with the land,” Guujaaw said. “It’s gonna take a long time to recover.”

Three days later came a significant step in that direction.

On Aug. 13, 2021, the governments of British Columbia, Canada and the Haida Nation announced a new framework agreement that recognizes the nation’s inherent title and rights across the archipelago of Haida Gwaii, which translates to “islands of the people” or “islands coming out of concealment.”

Hereditary Chief Gidansda, better known as Guujaaw, spent 13 years as president of the Council of the Haida Nation fighting for forests, fisheries and Haida title and rights. ‘We have to make things change.’ Photo by Jeffrey Gibbs.

Haida Gwaii is a collection of more than 200 islands forming an area about a third of the size of Vancouver Island and tucked under the Alaska panhandle. It’s home to some of the oldest and rarest plant and animal species on the continent, which the Haida consider their kin. This habitat of ancient rainforest, rugged coastline and surrounding waters teems with shellfish, shorebirds, five types of salmon and more than 20 species of whale, dolphin and porpoise.

On this territory, the Haida have endured a giant tsunami, an outbreak of smallpox that nearly wiped out their population and the onslaught of commercial hunting, logging and fishing that have shipped billions of dollars worth of resources off the islands. Even the remains of Haida ancestors have been literally robbed from their graves.

The first thing a traveller notices when setting foot on the islands is just how remote they are. It takes eight hours to make the 90-nautical-mile crossing from Prince Rupert on a ferry that rarely catches sight of land. Haida Gwaii is home to one of Western Canada’s largest populations of bald eagles, half the world’s ancient murrelets, and a host of other threatened and native species from the adorable Haida ermine to the largest black bear in the world (taan to the Haida, or Ursus americanus carlottae to zoologists).

In 2002, the Haida filed a title claim in the Supreme Court of British Columbia that declares authority over the land, inland waters, seabed, sea and airspace of Haida Gwaii. Despite meeting international principles for native claim, Canadian law has required Indigenous nations in B.C. to prove their continuous existence, use and occupation prior to 1846 — the year the British Crown asserted “sovereignty” (or sole jurisdiction) over “British Columbia.” Crown sovereignty is based on the discredited Doctrine of Discovery, which has allowed white settlers to magically become masters over much of the world.

The Haida possess a mountain of oral, written and archaeological evidence that shows occupation and use as far back as 12,800 years ago. The sheer remoteness of their home, like a fortress surrounded by a raging moat, has meant there are no overlapping claims by other nations. The archipelago was near impossible for all but the Haida and their canoes to reach.

Because the Haida have such a strong title claim, the court case has been a negotiation tool in the nation’s back pocket for the past 20 years. It has yet to go to trial — which could send shock waves throughout the Indigenous world if title is granted — but the Haida have never stopped pushing toward that aim.

However, the new GayGahlda “Changing Tide” Framework for Reconciliation unveiled Friday charts an alternative course that prioritizes negotiation over litigation while saying the two can coexist. The crucial part is the starting point. Instead of having to prove title, negotiations will now begin from a place of inherent Haida title and rights, which includes the right to self-government.

“GayGahlda represents an important opportunity to begin the process of Tll Yahda (“making things right”) between the Crown governments and the Haida Nation,” said Gaagwiis Jason Alsop, president of the Council of the Haida Nation, in last Friday’s announcement. “By shifting away from the denial politics of the past and moving to a place of truth through acknowledgment of inherent Haida title, a strong foundation for negotiations is established.”

A glassy morning on Skidegate Inlet exemplifies one of Haida Gwaii’s translations, ‘islands coming out of concealment.’ Photo by Serena Renner.

(Read the full feature, published August 19 2021, at The Tyee.)