Jonathan Franzen birdwatching in Spain. Photo courtesy of Andreas Meissner.

The author talks birds, failure on climate action, and finding meaning in dark times.

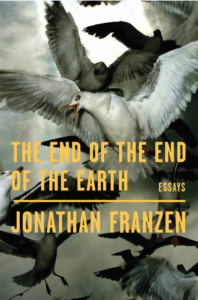

Whether he’s writing about the ills of consumerism, our addiction to technology, or the demise of complex discourse, novelist and essayist Jonathan Franzen has a knack for hitting America where it hurts. In his new essay collection, The End of the End of the Earth (released from FSG in November), the author most celebrated for The Corrections and Freedom treats everything from endangered seabirds to our collective inertia on climate change action with his trademark tonic of brutal honesty wrapped in stunning prose.

The collection contains several passages that are hard for an environmentalist to swallow—they detail the author’s hopelessness about our ability to avert catastrophic climate change. Not surprisingly, some of the essays—namely “Save What You Love,” a slightly edited version of Franzen’s controversial New Yorker piece “Carbon Capture”—have received backlash from prominent environmental activists including Bill McKibben.

But sharing nonconforming opinions and making oneself vulnerable to criticism is precisely the point, Franzen states. The essayist is like “a firefighter, whose job, while everyone else is feeling the flames of shame, is to run straight into them,” he writes in the book’s opener, “The Essay in Dark Times.” While social media tends to confirm one’s own biases, literature “invites you to ask whether you might be somewhat wrong, maybe even entirely wrong, and to imagine why someone else might hate you.” For every instance of hate or despair, Franzen delivers empathy, hope, humor, and a whole lot of love, especially for the book’s most prevalent characters: birds.

In December, Sierra had the chance to sit down with one of America’s most acclaimed living authors and birdwatchers at his home in Santa Cruz, California. Aided by deep breaths and closed-eye pauses, Franzen shared his thoughts on facts versus fiction, conservation efforts in the age of climate change, and of course, his beloved feathered friends.

***

Sierra: Your new book of essays, The End of the End of the Earth, covers a range of subjects, from your love of birdwatching to climate change, and from the importance of literature to the essay itself. What is it about writing essays that has always been a draw for you?

Jonathan Franzen: It takes pressure off the novels. I can write discursively about ideas without having to load all of that onto a fictional story. I think the only reason an author should ever put a personal opinion in a novel is to try to talk himself or herself out of it. Otherwise, who exactly are you ranting at? I think of the reader as my friend, not as some clueless person who needs to be socially or politically enlightened. But the rules are different in an essay. There, I get to talk about myself in my own voice, and I don’t have to hide my opinions, although I still might talk myself out of them. This tends to happen especially in a reported essay, where I start out really angry about something and then meet some of the people I’m mad at. It’s hard to keep hating people once I’ve met them in person.

Birds star in many of your essays. How did you go from being a bird appreciator to a bird lover?

I loved the outdoors when I was young, but my direct experience of animals was very limited. My most intense animal relationships were with plush toys and the Talking Animals in the Narnia novels. I think I always had a feeling that animals were fundamentally dear to me, but I didn’t make the connection between them and the natural world until I came to Santa Cruz in 1998 and started living with a real animal-loving person. Almost immediately, I started paying attention to birds. It was really love at first sight. I remember, the week after my mother died, in 1999, sitting all day and looking at the birds at my brother’s house near Seattle. I was watching the towhee, the flicker, the goldfinches. There was a pheasant, for God’s sake—not a native species, I know, but incredible.

You’ve written about your particular affection for seabirds. Why is island restoration important for seabird conservation?

Seabirds need friends because no one sees them. They could disappear entirely and very few people would even notice. That’s one of the reasons I like the nonprofit Island Conservation. It’s working in out-of-the-way places, and it’s addressing the number one threat to seabirds, which is invasive species on their breeding grounds. You have this amazing dimension of the animal kingdom, covering nearly three-quarters of the earth’s surface, and their global population has fallen by 70 percent in the past 50 years. More than half of all albatross species are now at risk of extinction, and most of the losses are happening on the islands where they breed. Removing invasives from islands produces excellent results per dollar spent if you’re concerned about extinctions.

Light-mantled Albatross off South Georgia Island. Photo by David Will/Island Conservation.

One of the central questions of the book is, How do we find meaning in our actions when the world seems to be coming to an end due to climate change? How did you arrive at your stated answer: focusing on smaller-scale projects that allow you to see tangible benefits in the present?

The analogy for me is that we’re all going to be dead before long, but this doesn’t stop us from trying to help the people we love. In fact, it makes us want to help them all the more. And we tend to love what we’re closest to—both the people and the species. There was this terrible stretch of utterly degraded shoreline on San Francisco Bay, near the old Candlestick Park, and some people there got the idea of spending every Saturday cleaning it up. They hauled out the megatrash, they worked on the smaller trash, and then they started pulling out invasive plants. And now the place is full of life again. You can say, “Well, my God, in 40 years, it’s all going to be under water. What’s the point?” The point is that those volunteers made a real difference. Obviously, the bigger picture is still important—it’s not an either/or. But if you’re honest with yourself, the bigger picture is pretty bleak, and you still have to live. You still want to do something meaningful for the people and the animals you love.

When I was a young man, I thought, well, first we need to kill the beast of technoconsumerism, and then we might start making the world a better place. Now it turns out the beast isn’t so easy to kill, but I refuse to give up on birds and their habitat. I’ve been alarmed about climate change for 25 years, and as long as it seemed like we would be able to do something about it, you could argue that that was the only battle to be fighting. Unfortunately, we failed to win it.

“I’m skeptical about a movement that seeks to dismantle the capitalist world order in the next few years, and that imagines that human beings are fundamentally rational and nice and only the carbon industry is evil.”

(For the full interview, originally published on January 7 2019, visit Sierra.com.)